Valiullina and Others v. Latvia Nos. 56928/19, 7306/20 and 11937/20, ECtHR, Fifth Section, 14 September 2023

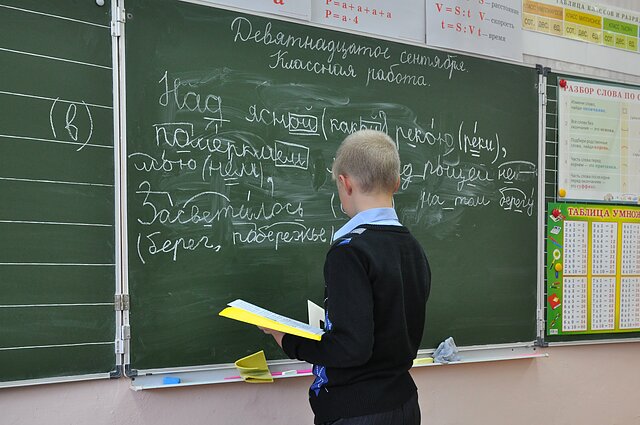

The European Court of Human Rights recently delivered a significant ruling on discrimination and the right to education. The case submitted to the Strasbourg Court concerns the Latvian legislative reform which, in 2018, provided for an increase in the percentage of subjects taught in Latvian in public schools and restricted the use of the Russian language. According to the applicants, the reform led to a negative effect on educational opportunities for native Russian-speaking students, discriminating against them on the access to education.

The Strasbourg Court recalls the conclusions adopted in the Belgian linguistic case (Case concerning certain aspects of the language regime in education in Belgium, Nos. 1474/62 and 5 others, ECtHR, Plenary, 23 July 1968) and confirmed on several subsequent occasions ( ex multis Cyprus v. Turkey, No. 25781/94, ECtHR, Grand Chamber, 10 May 2001; Catan and Others v. Republic of Moldova and Russia, Nos. 43370/04, 8252/05 and 18454/06, ECtHR, Grand Chamber, 19 October 2012) for which the right to education provided for in Article 2 of the First Additional Protocol to the ECHR would be meaningless if it did not imply, for its holders, the right to receive education in the national language or one of the national languages, without requiring States to respect the linguistic preferences of parents for education or teaching.

On this basis, the Court considers that, Latvian being the only official language of Latvia, the applicants could not, relying on Article 2 of Protocol No. 1, complain of a reduction in the use of Russian as the language of teaching in Latvian schools. And since the applicants did not put forward any specific argument in support of the claim that the restrictions had had a negative effect on their educational opportunities, the Strasbourg Court considers that the application based on the breach of Article 2 of the First Additional Protocol to the ECHR is not admissible.

As to the alleged violation of Article 14 ECHR in conjunction with Article 2 P1 ECHR, and thus the existence of discrimination based on the language of education, the Court considers that the difference in treatment introduced by the 2018 legislative reform is justified by a legitimate aim. According to the Court, considering the historical factors that significantly restricted the use of Latvian in the country for more than fifty years, during which Latvia was illegally occupied and annexed to the Soviet regime and the Russian language was imposed in many areas of everyday life, the need to protect and strengthen the Latvian language corresponds to the pursuit of the legitimate aim of preserving national identity.

A second legitimate aim also exists in the need to ensure the unity of the Latvian educational system. In contrast to other cases examined by the Court, where allegations of discrimination in access to education are linked to the existence of separate schools or classes for members of historically and socially disadvantaged groups (ex multis, D.H. and Others v. Czech Republic, No. 57325/00, ECtHR, Grand Chamber, 13 November 2007; Oršuš and Others v. Croatia, No. 15766/03, ECtHR, Grand Chamber, 16 March 2010; Elmazova and Others v. North Macedonia, Nos. 11811/20 and 13550/20, ECtHR, Second Chamber, 13 December 2022), in the case at hand, one of the objectives of the legislation is to facilitate equal access of pupils to public education and to erase the consequences of segregation that had prevailed in education under the Soviet regime, by guaranteeing equal opportunities for all pupils.

The legislative reform is considered by the Court to be also proportionate to the aim pursued. Indeed, it was adopted at the end of a gradual process that led to changes that were far from unexpected and sudden. As early as 1991, Latvian law had already enshrined the principle that everyone should be taught in the official language, and all subsequent amendments to the law on the subject have been widely debated in the social context to ensure a gradual increase in the use of Latvian as the language of education in public schools. Moreover, the 2018 reform did not completely abolish Russian as a language of education; it allowed teaching in Russian at the primary school level and provided that, at the secondary school level, special subjects related to Russian language, identity and culture could still be taught in Russian. The implementation of the reform also took place flexibly and with sufficient room for adaptation, depending on the needs of the individuals concerned and allowing pupils who needed it to adapt to the new situation and to take steps, if necessary, to improve their knowledge of the official language. At the same time, the reform ensured the use of minority languages in varying proportions, depending on the school and the class in which the pupil was enrolled, while maintaining the possibility for Russian-speaking pupils to learn their language and preserve their culture and identity.

In that sense, it may be held, according to the Court, that the Latvian State established a system of teaching in the official language of the State with respect for linguistic minorities, justifying the need to increase the use of Latvian as the language of education in the school system in an objective and reasonable manner.

On these bases, the Strasbourg Court considers that there is no breach of Article 14 ECHR, read in conjunction with Article 2 P1 ECHR, where the respondent State did not exceed its margin of appreciation and the difference in treatment introduced was compatible and proportionate with the legitimate aim pursued.

(Comment by Nadia Spadaro)