Nepomnyashchiy and Others v. Russia, Nos. 39954/09 and 3465/17, ECtHR (Third Section), 30 May 2023

The ECtHR dealt with hate speech in the case Nepomnyashchiy and Others v. Russia on 30 May 2023. The decision is a significant contribution to the legal debate on pluralism and hate speech. The case involved homophobic statements by high-ranking politicians in interviews to leading newspapers in 2008 and 2013.

The applicants lodged an application to the ECtHR complaining about the violation of their right to respect of private life (article 8) in conjunction with the prohibition of discrimination (article 14). Precisely, they held that state officials’ negative statements constituted a call for violence against LGBTI people, thereby discriminating against them as LGBTI rights activists and members of the LGBTI community. The applicants further alleged that the domestic authorities had failed to protect them from discrimination. In fact, their criminal complaints were not followed by any proceeding and a civil complaint was also unsuccessful.

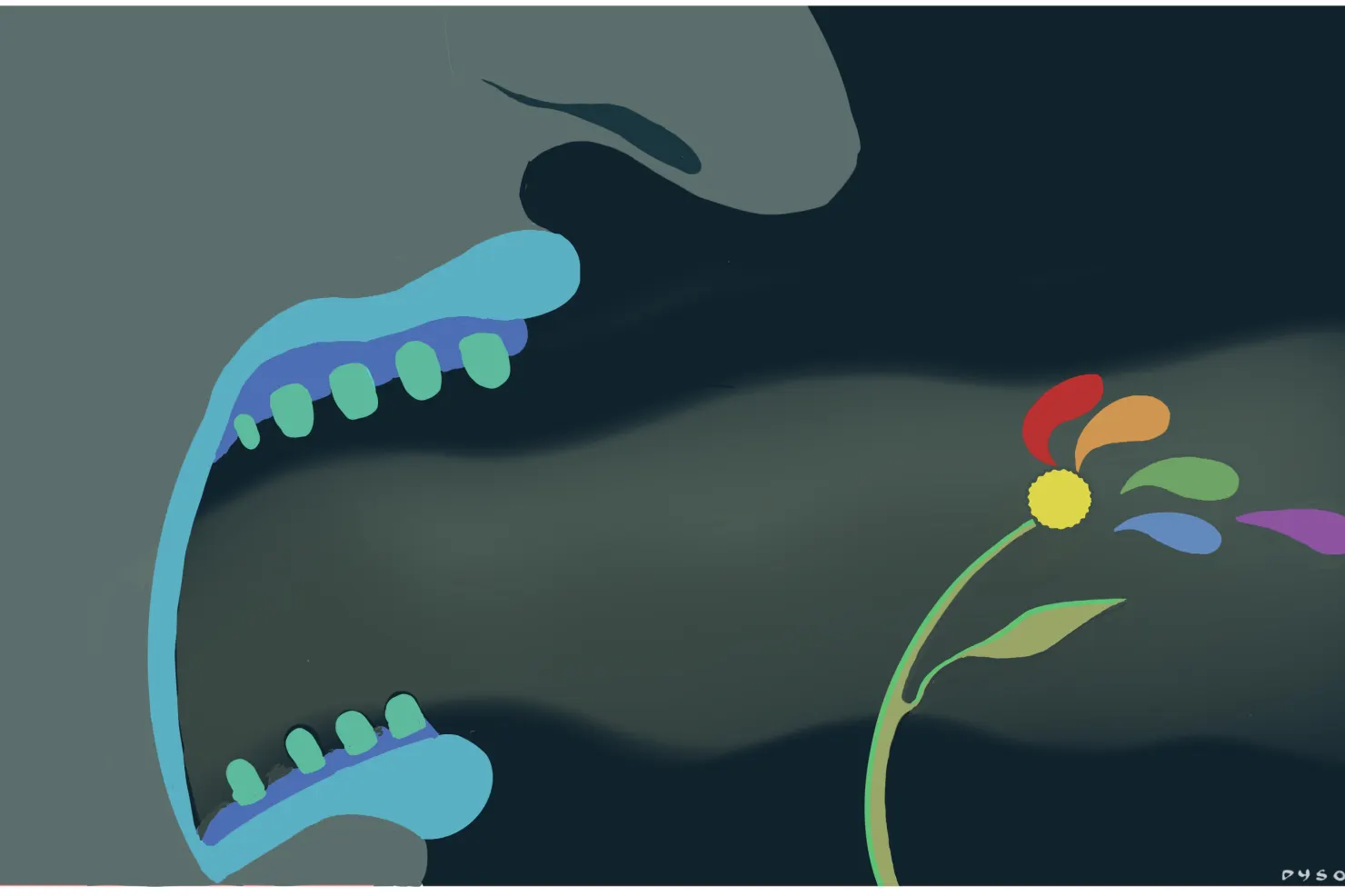

The ECtHR first established its jurisdiction to examine the applications as the facts giving rise to the violations took place before 16 September 2022, the date on which Russia ceased to be a Party to the Convention (paragraph 51). It then described the context. The negative statements were made by two influential public figures holding official posts, namely a member of a regional legislative assembly and a regional governor (paragraph 61). Published in popular newspapers with a wide audience, the interviews portrayed a sexual act between two men ‘as repulsive and disgusting as a murder’ (paragraph 15). The politicians made other statements such as: ‘Tolerance? Damn it! Homos must be torn to pieces. And the pieces thrown to the wind!’ (paragraph 5); ‘these are not human rights, these are rights of sickos and perverts’; ‘why should the advertising of alcohol and beer be prohibited, while the advertising in front of children of the merits of being gay and of the equivalences of same-sex families and normal families should not be?’ (paragraph 15).

As to the targets of the negative statements, the Court identified that the Russian LGBTI community constitutes a ‘particularly vulnerable group needing heightened protection from stigmatising statements,’ given the ‘history of public hostility towards the LGBTI community in Russia and the increase in homophobic hate crimes’ (paragraph 59). The Court further maintained that the contested statements had affected a core aspect of the identity and dignity of LGBTI people, thereby reaching the threshold of severity required under Article 8 (paragraph 62). Belonging to the LGBTI community and being LGBTI rights activists, the applicants were thus entitled to claim to be victims of a violation of Article 8,

Finally, the ECtHR recognised Russian authorities’ failure to provide an effective legal response to hateful statements. While Russian Law provided for civil-law and criminal-law mechanisms for the protection of one’s private life against this type of statements, their effectiveness in practice was, the Court argued, questionable (paragraphs 79, 85). In conclusion, the ECtHR found a breach of the prohibition of discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation in the context of the right to private life (Article 14 and Article 8).

(Comment by Giovanna Gilleri)