The UN Intersectionality Resource Guide and Toolkit

The Intersectionality Resource Guide and Toolkit is a document drafted by UN Women—the United Nations agency dedicated to gender equality and women's empowerment—in collaboration with the United Nations Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNPRPD). The guide aims to help organizations and individual professionals introduce intersectionality into policies (as a tool to improve the focus on marginalized people) and programs (to integrate the processes of design, implementation, and evaluation).

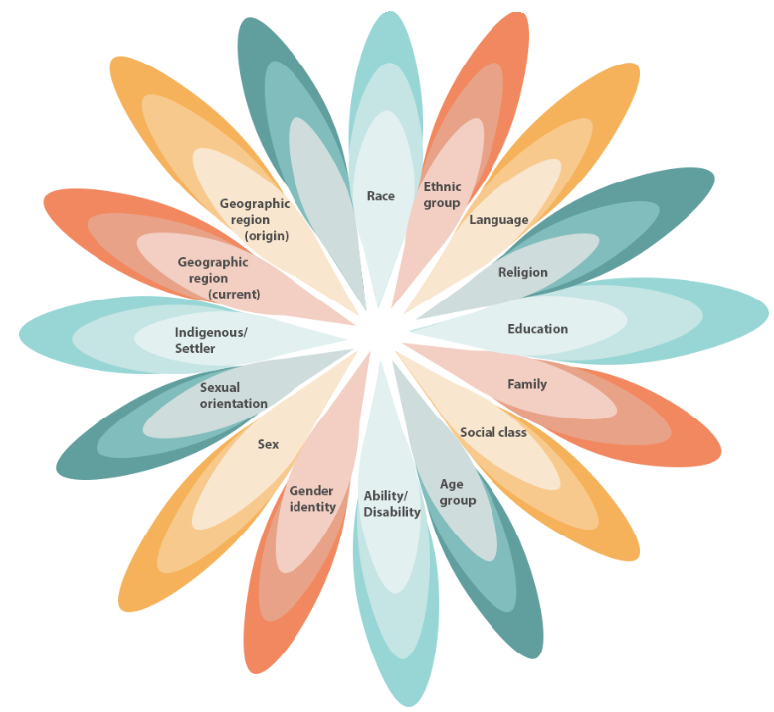

As is well known, the term intersectionality refers to an analytical and theoretical approach that considers how different social identities (e.g., gender, ethnicity, social class, disability, sexual orientation, age, religion) combine and interact with each other to produce specific experiences of advantage, disadvantage, or discrimination. Originally coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, the concept was developed to show how black women in the United States were often excluded from legal protections and feminist and anti-racist discourse, as anti-discrimination policies and laws tended to consider gender and race separately. Since then, intersectionality has become an analytical lens that, starting with law, has become central to many fields such as public policy, sociology, and inequality studies.

One of the most common criticisms levelled at this successful concept concerns the difficulty of translating theoretical complexity into empirical analysis tools. In this regard, the document drafted by the United Nations aims to bridge the gap between theory and operational practices, anchoring intersectional lenses to the interventions necessary to achieve the objectives of Agenda 2030. In other words, the aim is for interventions to truly enhance pluralism and enable, as envisaged by Agenda 2030, that no one is left behind..

The practical approach can be adapted to the needs of each working group as it suggests concrete ways to create spaces for reflection in operational practices and, at the same time, serves as a guide for making adjustments, reorienting policies and programs to include intersectional identities that were previously hidden or silenced.

The attempt to “ground” a concept that originated and developed in academia starts from the identification of eight dimensions to be integrated into each phase of policy and program design, implementation, and monitoring. The most interesting element of this section is that questions are proposed for each of the dimensions to stimulate the adoption of new lenses for observing inequalities. Among others: "Who is included or excluded from this intervention? What intersectional identities influence access to resources and power? What norms, practices, or policies maintain these inequalities? How do historical, cultural, or spatial conditions affect the experiences of those involved? How does our organization reproduce or counteract these dynamics?

In relation to the analysis phase that precedes each intervention, these questions stimulate the working group's reflectiveness and encourage advocacy for marginalized people, involving them from the early stages of planning, according to the principle of “nothing about us without us.” This is followed by the implementation phase, in which it is necessary to ensure meaningful and non-symbolic participation by marginalized groups, promoting flexibility and the possibility of adapting the system adopted. Finally, the document suggests that monitoring and evaluation should also be carried out according to participatory logic, measuring not only the number of beneficiaries but also their intersectional characteristics and changes in power relations.

To give an idea of the pragmatic approach of the guide, one of the tools it includes is the “Power Flower,” an activity lasting about two hours, useful in the early stages of setting up a working group, aimed at a maximum of 25 people. Under the guidance of a facilitator, each participant reflects on their multiple identities, how they combine with power relations (privilege, advantage, exclusion) and how they influence the way they “are” and “act” in professional and intervention contexts. The exercise helps to focus attention on the subject who intervenes (who am I, what positions do I occupy) before planning interventions on others: this promotes greater self-awareness and less risk of reproducing exclusion. Thanks also to visual language, it encourages the transition from a monolithic view of inequalities to a multiple view of identities, both at the intersectional level and in terms of power relations. Finally, it encourages active participation, dialogue, and open discussion among participants, improving the quality of the project or policy that will follow.

(Focus by Oriana Binik)

Selected bibliography:

H. Al-Faham, A. M. Davis, R. Ernst, Intersectionality: From theory to practice, in Annual Review of Law and Social Science, n. 15(1)/2019, 247-265.

S. Cho, K. W. Crenshaw, L. McCall, Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis, in Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, n. 38(4)/2013, 785-810.

P. H. Collins, S. Bilge, Intersectionality, John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

K. Crenshaw, Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1)/1989, 139–167.

K. Crenshaw, Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color, Stanford Law Review, 43(6)/1991, 1241–1299.

O. Hankivsky (ed.), An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework, Vancouver: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University, 2012.

O. Hankivsky (ed.), Intersectionality 101, Vancouver: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University, 2014.